> [Archived] Interviews

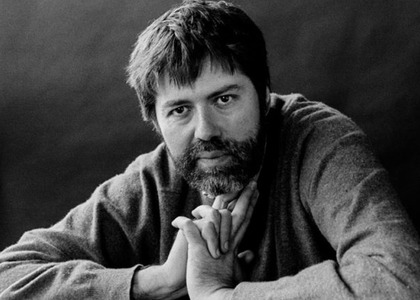

Interview with pianist Andrei Vieru

The Paris-based musician and writer was invited to the Meridian Festival

Mr. Andrei Vieru, you will perform a recital marking 20 years since your father, composer Anatol Vieru, passed away. In your essays, we sense a very strong father-son relationship. Anatol Vieru was your personal and professional role model. Now, 20 years after his passing, how would the son put his father's portrait into words?

The first book I published begins with a portrait of my father, a moral one, not physical. Out of everything I have written, that chapter, that portrait, was the most costly. I remember what he said once: "Success, very well! But not by all means!" This says a lot about him, I think. It was actually a time when everything went from one extreme to the other very fast and very intensely. It was after the war, when composers seemed to avoid success by all means; they wanted to shut themselves in an ivory tower to keep themselves away from the general public as radically as possible - a sort of ultra-elitism. Then they quickly went to the other extreme, to success by all means. They got somewhat scared of how well they managed to shut themselves away in that ivory tower. I think my father never went to either of these extremes. Of course, he occasionally composed a more experimental kind of music too, but part of his music is actually very accessible; and when it is less so, it's because that's what he felt like writing. Out of my three main criteria for judging music, I don't know whether they were his too (maybe I "inherited" this idea from him), namely originality, authenticity, accessibility… I think he valued authenticity the most. Not that originality and accessibility are not important, but they should be somehow subordinated to authenticity. Now, I don't know to what extent I'm also talking on his behalf when I say this, but I believe I'm being fairly faithful to him when I attribute this esthetic and ethical vision to him.

I never heard him speak ill of other people. Last night, for example, I was out with my friends and someone said: "I read so-and-so book. So-and-so's image has been torn apart." And another one says: "My friend, I have no interest in books who tear people's images apart." This is how I remember my father. He had no interest in tearing people apart. He had no such pettiness. Of course, he had a very critical and lucid eye; he could perfectly tell what was going on around him, generally, as well as in detail, but he never wasted his time with this. He worked all the time. For this reason, he had no time to put on social masks. He was somewhat engrossed in whatever obsessed him; that is, music, actually. We were, indeed, very close. I can't remember now, maybe there is a gap in my memory, but I can't remember him ever explaining anything to me.

He conveyed it to you without words.

Yes. But out of all the people who played a role in my development, his role is the most important.

Mr. Vieru, what will you perform during the homage recital to Anatol Vieru on Sunday?

Verses, a piece for violin and piano, with Diana Moș, with whom I have the pleasure of performing for the first time. It's a piece that's very dear to my heart. I have never played it before, so from this point of view, it's a first for me also, but I know the piece - I know it by ear and by eye. I have long wished to get the chance to perform it and I am very happy to be able to do that now.

Translated by Mădălina-Andreea Grosoiu, MTTLC, 1st year