> [Archived] Chronicles

Premiere of Turandot. The National Opera of Bucharest is not the Metropolitan Opera of New York. Therefore?

...therefore I think we should be content with what we have. We can still hope for a better future. If we desband, offend, destroy, condemn... even rightfully, we might be deprived of the very object of our contempt. Would Bucharest be a better and more beautiful place without the shows of the National Opera? Definitely not. That the productions can - and must! - be better, fro all points of view, is a fact I will not dare deny. But with its most recent premiere, Turandot by Puccini, the National Opera proved its capabilities. It offered us the best it can offer at this very moment. And we must appreciate the gesture. Even though...

Turandot is a work in which any international lyrical stage takes pride. Being able to present Turandot automatically moves the scene to a superior league. It's a difficult score for everyone - both the singers and the instrumentalists. Its author left it unfinished, with unpolished details... For the old master, tortured by the pain of an unforgiving disease, the battle with the Chinese fairytale, with all its facets, is increasingly difficult. Especially as it's the first time that Puccini works with a... story. An Oriental fairytale, whose plot is set in a faraway land, in an undefined era - Cio-cio-san did exist in Nagasaki in 1904, Tosca did love and die in Rome on June 17th and 18th, 1800, and Mimi did walk around Paris in 1830. But what about Turandot? Princess Turandot? And Prince Calaf? And Liu, the slave? According to the indications in the libretto, they lived in Pekin, China, in legendary times. Times that Puccini, through his music, has to contour and give life and personality to. And he does this in a masterly way, with the atistry and inspiration of a genius. The melodies and harmonies flow by themselves, the elements specific to the Chinese sound universe give colour and identity to the music, a whirl of immense force to which you, as part of the audience, must surrender entirely. And you do so, with great pleasure, seeing how the Ice Princess Turandot - who has no mercy in sending to death the ost handsome princes that propose to her, but aren't able to solve her riddles - ends up defeated by the force of a brilliant intelligence and a passionate love.

The story leaves the director, the scenographer and the costume designer with an extremely generous space for creation. The only thing that Puccini didn't quite take into consideration is... the singers' throats. That's why staging a Turandot show is an adventure with an unpredictable end. But the theater that dares to do it, has to take the consequences. We've had huge interpreters fighting and winning before Puccini's score - the tenor Ludovic Spiess was a Calaf as rarelycan be seen. The Romanian artist sang this part and was acclaimed on the greatest opera stages in the world. Another memorable interpretation of Turandot was that of Mariana Stoica. As far as I know, Maria Slătinaru Nistor sang the part only in a concert version of the opera, but this doesn't affect the exceptional success in any way. It was happening in Bucharest in the '70's. However, today… it seems that Turandot - and not only - can be sung in Bucharest only with guests. But there's nothing to be ashamed of. You can't always find a Turandor, an Elisabetha, an Elsa, a Calaf, an Otello… The works appear in the repertoires but they're only sung when the local cast can be completed with foreign voices.

Meeting Puccini's music is always a celebration, for both the connoisseurs and the amateurs of lyrical theatre. The premiere I watched at the National Opera on Friday, February 14th, had was sold out. And the applause was honest and enthusiastic. Only few of us noticed - and, in the end, appreciated - the singers' battle with the score, the huge amount of effort, the visible exhaustion, the fear masked by a scenic easiness or, on the contrary, by static poses where you do nothing but try to sing and hold on until the end of the show. Only few of us were bothered by the rudimentary directing (I wonder why this Italian - with such poor artistic record, who has already proved, on the stage of the National Opera, in important shows such as Don Carlo, Tosca or The Troubadour, how little he knows and can do - is once again called upon in the same quadruple position of director, scenographer, costume designer and lighting director, for what should have been a mega-production with Turandot?!); by the unimaginative setting, the huge and inconvenient stairs - a naive representation of the permanent come-and-go between the vulgar world and the divine one; by the absolutely unidentifieble object placed at the top of the stairs - a chained heart, a snake egg??! (see explanations in the flyer) - which all those enteing the stage have to bend in order to awkwardly avoid, therefore their grandeur is strongly affected; by the fact that a small group of dancers cannot raise an arm or a foot at the same time, thought they should; that Liu, the slave, who's been accompanying her master in exile for so long, on dusty country roads, wears an immaculate white princess gown - yes, I have thought of white symbolizing purity, but still... we're not kids anymore! - and she plays/mimics her part with outdated and stereotypical movements that the civilized world of musical theater no longer accepts for decades now. ...and there would be some things left to say.

However, I will stop here, as old age leads you, after a while, to accepting that you can look at the glass from two different perspectives - either see it as half full or half empty. As for the orchestra, many times the overflow was so abundant that it drowned the stage and the singers. The music allures you... Puccini charms you!would be the most plausible explanation, though, of course, unsatisfactory. The singing was loud, loud, loud... with bright brass and plenty of percussion intruments. And that appeals to the audience who enjoyed the show, especially after receiving the long-awaited high note in Nessuna dorma, an aria known - Pavarotti is to blame! - by anyone. All in all, we have Turandot in the repertoire of the National Opera. With its ups and downs, but...we have it. We must agree that this is beneficial for both the National Opera and the audience. Because, after all, Puccini's music end up victorious.

This morning, I read something on facebook that the MET considered necessary to share: in the show with Agrippina by Handel, the royal costume also contains a crown, an extraordinary jewel designed after St. Edward's Crown, the central piece of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdon of Great Britain, for which a consistent team of professionals worked for over a month. It's just a constume detail! We had our own golden drops in the tiny costume of the Persian prince and, at the end of Turandot, when gilded paper confetti were thrown on the stage in plenty (to the audience's delight, we must admit!), Maestro Mario de Carlo could have never met this on the MET stage! But the National Opera of Bucharest is not MET. And not can it be. For now, we're content with what we have. Because, without the National Opera, everything would be even sadder! But we're not losing hope for a long-desired better future.

National Opera of Bucharest

Premiere

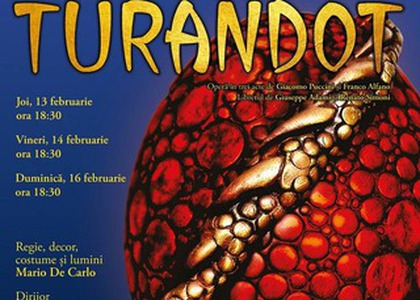

Friday, February 14th, 2020, 6.30 PM

TURANDOT

A three-act opera by Giacomo Puccini

Libretto by Giuseppe Adami and Renato Simoni

Director, setting, costume designer and lighting director - Mario De Carlo

Conductor - Tiberiu Soare

Choreography - Corina Dumitrescu

Choir master - Daniel Jinga

Children's choir master - Smaranda Morgovan

Director's assistant - Alexandru Nagy

Cast

Turandot - Dragana Radakovic - guest

Altoum - Ciprian Pahonea

Timur - Marius Boloș

Calaf - Adrian Dumitru

Liù - Crina Zancu

Ping - Florin Simionca

Pang - Lucian Corchiș

Pong - Valentin Racoveanu

A Mandarin - Dan Indricău

Translated by Eleonora Manea, Universitatea București,

Facultatea de Limbi și Literaturi Străine, MTTLC, anul I