> [Archived] Interviews

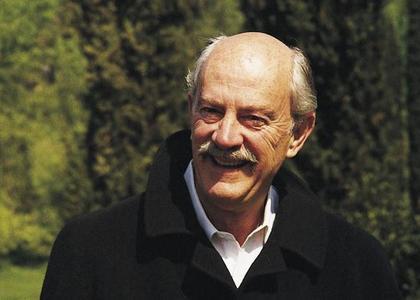

Interview with the Late American Conductor, Alan Curtis

The 15th July, 2015 is when Alan Curtis, the harpsichordist, conductor, musicologist, and founder of the Il Complesso Barocco ensemble passed away. He was one of the musicians who contributed to renewing the audience's interest in Baroque music, especially in Händel's creations. During the 2011 George Enescu International Festival, Alan Curtis performed the Ariodante opera with his ensemble. The following interview was taken by Maria Monica Bojin on that occasion:

Can you explain why pre-classical music has such a positive effect on us?

It has to do something with the era we're living in - I don't claim to know what it is exactly, but this is the way I feel. Pre-classical music was as chaotic, intricate and elaborate as the times we're living in; at the same time we have managed to find a certain order in it, which helps us cope with our problems.

So, Baroque music is chaotic? I would have thought it was one of the most organised forms of music!

It is a kind of music abundant in details from a psychological point of view - I believe this is an element that lacks in later music. It has a complexity which sometimes is organised and sometimes not, and I will say again that it is very similar to our lives nowadays.

A work that is performed on period instruments has a different impact on us compared to the same opus performed on modern instruments; many people find it to be more beautiful. Aesthetically speaking, what is the difference between the two?

First of all, using period instruments makes us re-think that particular piece of music. When performing on modern instruments, we're carrying a heavier 'baggage' from the recent past, so to speak. At first, I started studying the piano, and what I learned about this instrument and the art of playing it, had a great impact on my performing style. When I started playing the harpsichord, I had to rethink it; I had to start it all over again. I believe that this is one of the most important aspects of performing on period instruments: it helps us see thing differently and it also makes us find new solutions to older problems. I also believe that modern instruments are not as flexible, and therefore not as suitable for performing old music. For instance, both the violin and the bow have evolved, and the way in which one uses the bow nowadays is very different from the way it used to. Performing on period instruments makes us creative and ingenious, and these ideas come exactly from the pieces of music we perform, and not from the vision that we project onto that particular piece of music.

You ordered some instruments requesting them to be made the way they were made in the pre-classical era. Was using new materials to make period instruments difficult for the luthiers?

Yes, they encountered a few problems, but they finally realised they had to use the… original materials. Here's an example: so far, the chords of the harpsichords have been made of modern steel, which is a metal of few imperfections; well, we arrived at the conclusion that that particular type of chords didn't sound so well; the older, flawed chords - according to the modern vision - sounded a lot better exactly due to those imperfections! And now Il Complesso Barocco ensemble uses a type of chords made by an Australian luthier! So, it is actually possible to turn a disadvantage into an advantage. Yet another example: the modern trumpet has a certain opening that makes it easier to perform on while the authentic trumpet doesn't have it, but the quality of the sound is higher.

You specialised in Baroque music, but you also conduct Gluck, Haydn, and Mozart's creations. Have you ever been tempted to move on from this certain point in music history?

No, I'm very happy to stop at Mozart's compositions! Beethoven's early creations are also interesting, but he is a composer I admire, not love. Mozart's case is different, as I admire and love him as much as Händel or Monteverdi. It is a matter of personal taste, but it's also the fact that each man has certain limits regarding his feelings about music and the meaning it conveys. Most of 19th and 20th century music doesn't speak to me. I think I can understand it, I certainly appreciate it, but it does not convey deep messages to me, whereas Monteverdi's music speaks a lot to me - it's been over 40 years since I started studying it! I have recently conducted The Coronation of Poppea and so many new ideas occurred to me that I decided to work on a new interpretation of the score! This always happens when it comes to the music you love and you connect with - you always find new things about it. Ravel's Bolero is a famous work that I liked a lot when I was a teenager and I still do, but it offers me nothing more than the first time I listened to it. This means that it's not the right music for me.

This can also mean that Monteverdi, Gluck, and Mozart's works are actually contemporary!

They are, for me - they fit my lifestyle, my way of living, and my current experience in a way in which later music doesn't. I grew up with Stravinsky's The Rake's Progress, and I was thrilled when it was written! I took piano classes with Soulima, Stravinsky's son, and he lent me his copy of his father's works before being published. Therefore, my first contact with this kind of music was made through Stravinsky's signature itself - I still love that composition, but curiously, it sounds dated when I listen to it now, it sounds like the 50's, while Gluck and Bach don't sound like the 1700's; they sound like an unknown world to me, a world that I want to explore, a world full of meanings which has a lot to reveal to me.

Do you think that opera is the complete musical genre?

It is the most fascinating to me; it implies so many different things, of course. One of the reasons why I chose opera is that, when I was very young, I took interest in many subjects from various areas: arts, history, the beauty of the costumes and the art of acting. I'm telling you that back then I didn't enjoy opera at all! The first operas I watched seemed very boring to me. It took me a long time to become interested in them and, of course, Monteverdi was the one to strike a chord with me. I think I was about 25 - that is when my opera journey began. I have arrived to Mozart now, and I also enjoy other operas - Boris Godunov, The Rake's Progress - but for me, the real opera compositions are the ones between Monteverdi and Mozart.

You're bringing not only Händel, but also Ariodante to Bucharest. What defines this composer's operas?

By casting a superficial look on the operas themselves, one could tell that these works were mostly composed for the English audience, an audience that did not understand Italian very well, so, the recitatives were short and didn't tell a great story. They were works that combined a series of elements: they were written by a German composer for English listeners of musical works in Italian. The topics included magic and the supernatural and, they were neither real, nor contemporary. Händel didn't write any librettos, he used previously written texts that were already 60 or 80 years-old when he picked them. It seems so odd! And one might believe that his operas are totally uninteresting for this particular reason - this is actually what his listeners used to believe up to the early 20th century. About that time we started realising that Händel's operas had a very special trait that we hadn't noticed before, namely, they were psychological portraits.

The arias speak a lot about the personality of a character. They are the ones that build a very emotional, dramatic and spectacular atmosphere, because both the plot itself and the libretto do not necessarily create a great work of art. Sometimes they don't even make perfect sense at all, especially because Händel removed the very parts that explained the action - those shortened recitatives that made it easier for the English audience to understand them.

Out of Händel's 42 operas, the most meaningful and emotional is Ariodante. Many years ago, La Scala theatre in Milan asked me to select one of Händel's operas to perform there. I chose Ariodante, and that was the first time it was performed in Italy. Now it has become one of this composer's best known operas!

Why do you think that we still enjoy opera nowadays as much as hundreds of years ago?

We belong to an anti-classical era; this doesn't mean we are not very interested in classical music as organised, rational and classically-simple music - this is what Mozart's music is, and Mozart is really loved today. One of the musical genres in which Mozart composed is opera, and among his creations you will be able to find The Magic Flute - an entirely irrational and emotional work.

Händel is a composer who creates emotions, has a great imagination, and is not rational and logical at all. Among the various reasons why opera is so important to us nowadays is the fact that we have a high visual sensitivity, higher than it used to be in other ages. The endless lines of people queueing in front of museums, such as, the Ufizzi Gallery here in Florence where I am now, and the Louvre in Paris - are proof enough. People enjoy watching an opera; more than that, they enjoy picturing it according to their own imagination, and this is why operas in concerts have revived opera compositions unexpectedly, and have a great deal of attention being paid to them.

Moreover, many operas have simple stagings due to lack of money and alternately, for an opera in concert, money is not an issue anymore, and one can picture everything they hear as if described through music. For instance, the second act of Ariodante starts in a garden with gothic ruins and the moon is visible behind a thin cloud. All of these can be heard while listening to the music, so they can be visualised; this is why I believe that an opera in concert is more than a simple concert. It makes one's visual imagination collaborate with one's musical imagination.

Translated by Ioana Săbău and Elena Daniela Radu

MTTLC, the University of Bucharest